Headgear to Helmets is a documentary feature film that provides an insight into rugby league players who enlisted in the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps and saw active duty during the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign.

Headgear to Helmets: George Duffin

Headgear to Helmets: Stan Carpenter

Headgear to Helmets: Herbert Bolt

Headgear to Helmets: Tom Bruce

Headgear to Helmets: Paddy Bugden

The following story is the sixth in a series of six.

The short, extraordinary sporting career of Charles Savory spanned the Tasman, imposing a firm footprint on both rugby codes and within the square ring of boxing and wrestling. The big bloke from the Auckland suburb of Grey Lynn, was the Sonny Bill Williams of his time - pushing even SBW into the shade with the drama and controversy of a brief, incident-packed life which was ended by a Turkish shell at Anzac Cove on the Gallipoli Peninsula, on May 8, 1915. In the years before the 26-year old Lance Corporal Savory sailed to Gallipoli to `play the other game', he had represented both New Zealand and a famous Australasian team at rugby league.

The combined elements of Charlie Savory's sporting career, with its tragic finale, almost defy belief.

• A robust front-row forward, he was initially a rugby union man but was banned for two years in the 1910 season for allegedly kicking an opponent.

• Savory promptly switched to rugby league, joining Ponsonby Club, and relishing the rugged forward exchanges of the new game, was selected in 1911 for the New Zealand team to campaign in Australia.

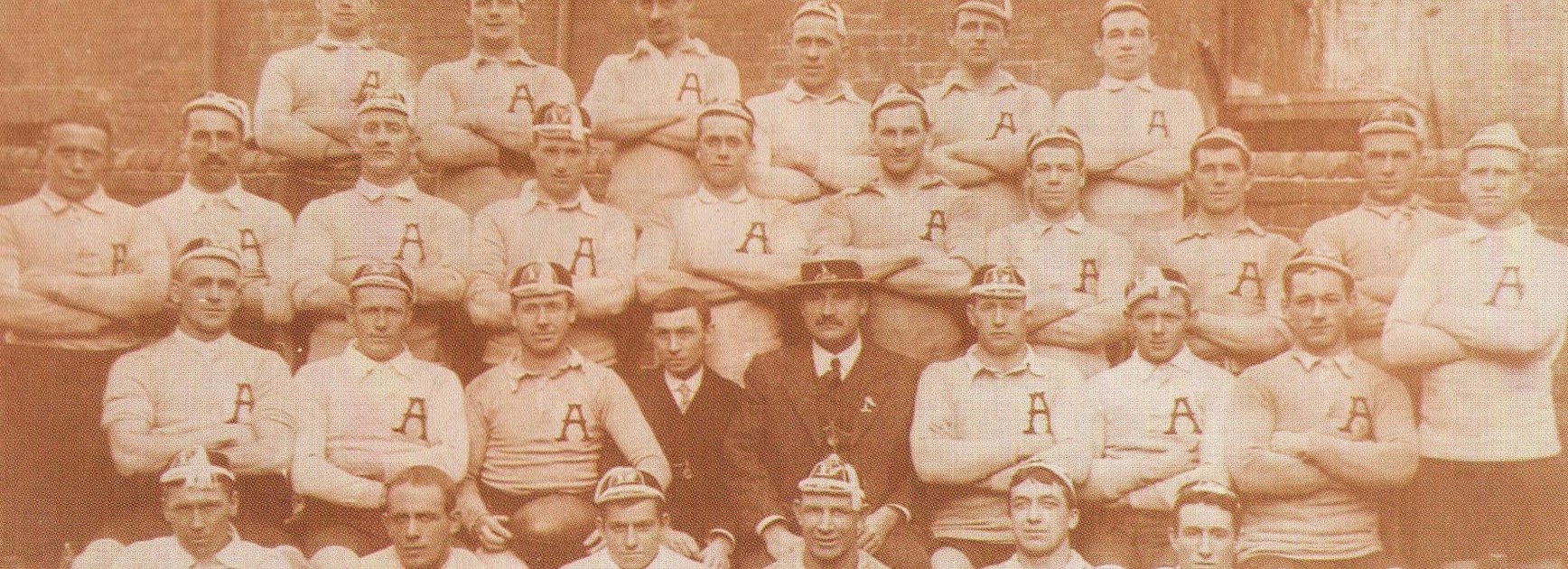

• So impressive was he on tour that he was then chosen as one of four Kiwis to make up the Australasian side which sailed to England aboard the RMS Orvieto in 1911 for a marathon campaign of 36 games, of which they lost only five. Brilliantly led by Glebe's Chris McKivat, the 1911/12 team won the `Ashes' against GB for the first time – and rate to today as one of the greatest of all touring sides.

• Back home in New Zealand in 1912, the robust Savory promptly headed into hot water again, being sent off in a club game and suspended for the rest of the season.

• Things only got worse. In season 1913, members of the Auckland Rugby League Executive accused Savory of kicking a Manukau opponent and disqualified him for life – leading to the greatest administrative upheaval in the history of league in New Zealand, with Savory eventually being acquitted of the charge (he had strongly argued `mistaken identity in the incident at issue) – and the NZRL disqualifying, and then replacing, the entire 14-man executive of the Auckland RL. The whole thing became known in NZ rugby league folklore as `The Savory Affair'

After all the drama Savory was able to get on with his rugby league career, winning a place in the 1914 Kiwi team, comprised of amateurs, which went within a whisker of upsetting the touring England side which had just beaten the Aussies in what became known famously as the `Rorke's Drift' series.

Soon afterwards, Savory, whose football playing weight was listed at 89kg (hefty in those days, if miniscule today) won the NZ Amateur Heavyweight Boxing Title; he had been bracketed with another fighter for national heavyweight honours as early as 1910. No mean grappler, Savory was also game enough to take on the wrestling freestyle heavyweight champion of the world George Hackenschmidt when the champ showed up in Auckland.

Savory was 25 when he claimed the heavyweight boxing title in 1914. But already the clock was ticking on a remarkably crowded life.

To shine a mirror back down the years on Savory is to reveal a controversial footballer but a genial larger-than-life character too, a man who was a `leader'.

One prominent official of his playing days described him as "a thorough gentleman on the football field." Another observation has him as "easily the most conspicuous figure on the field in almost every match he played. In every forward rush his burly figure was the anchor." A prominent NZ official from the 1911 campaign in Australia called him "the gentleman of the team, a happy go lucky fellow, the best forward we took away with us and a father to the boys.

Savory was an outgoing character, and in the reports from aboard the Orvieto en route to England in 1911 during which the players regularly attended concerts and dances, he was one player who would always provide a `turn', with his speciality being a rendition of `Swanee River".

The long haul of the tour of 1911-12 must have been a frustration for such a man. He would play only four of 36 matches, having suffered a fractured hand in his first game. From the distance of the years it can only be presumed that the break was a particularly bad one

On the outbreak of War in 1914, Savory enlisted with the Auckland Infantry Regiment and departed to Egypt with the main NZ Expeditionary Force. A note in records provides a snapshot of the imposing nature of the man: "Such was his physique that when he went into camp he had to wear civvies for a few days while a large enough uniform was made for him."

In Egypt en route to Gallipoli his leadership qualities emerged when he helped organise two 15-a side games against artillery men camped at Zeiton near Cairo. The teams drew one game and Auckland took the decider 6-3. "Never in all its history had the Egyptian Railway Ground seen such struggles," noted the regiment's official record.

From Egypt it was on to the War, to Ari Burnu at the north end of the Gallipoli Promontory and what would become known as the Second Battle of Krithia.

Leading NZ sportswriter and historian John Coffey has written of the fateful day Of May 8, 2015: of how Savory was "an inspiration to the nervous men around him as the boat approached Anzac Cove", writing: "Savory was fatally shot, when, despite not being required to go ashore, he announced, `I am going to fight for my country' and led the charge to the beach."

Via appalling administrative mismanagement it would be 14 weeks before the official confirmation of Charles Savory's death on that morning reached his family and army of friends back home.

Repeatedly he had been reported `wounded' in various official correspondences - such as this, weeks later, to the family: your brother has not been reported since the 15th May - you may conclude that his case is not one for anxiety". Eventually letters from the Dardanelles confirmed that he had been one of the first of the New Zealand contingent killed – by a shell to the head. "A terrible sight," wrote A.V Cross, a Newton Rangers footballer also serving on the front.

Savory, such an extraordinary figure in early football featuring the trans-Tasman neighbours, had lived so colourfully – then died so suddenly and shockingly.

# On 26th August 1915 in the newspaper The Grey River Argus, there came a remarkable post-script - a story under the headline `Drowning a Turk' which, whatever its veracity, added a final strand to the tale of Charles Savory. The story told of a struggle at Gallipoli between two soldiers, an Australian and a Turk, both of them big men, which ended in them tumbling together from a cliff top into the sea. There, after a fierce struggle, it was reported, the Australian drowned the Turk. The newspaper' source was the Auckland representative of the Otago Daily Times based on correspondence from an `Auckland doctor writing from the Front' who declared that the Allied soldier was not an Australian - but was, in fact, Charles Savory!